You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘UK’ tag.

It’s no secret I am a fan of Flickr Commons. The UK National Archives just went online.

George Davey was sentenced to one month’s hard labour in Wandsworth Prison in 1872 for stealing two rabbits. He was ten years old. (Source)

Last month, spurred by Michael David Murphy‘s summary opinion piece I started writing about photographers rights.

I have talked before (and here and here) about the diminished freedoms for photographers in the UK. While the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) led many of the actions, it is the support of the whole photographic community that has driven the issue.

The half-penned piece was rendered redundant by last weekend’s “I’m A Photographer, Not a Terrorist” demonstration in Trafalgar Square, London last weekend. The event looked like a hoot (see here, here, here and here)! Nevertheless, I want to throw down a few thoughts and some links.

ONGOING CONFUSIONS

In November 2009, the UK police issued a memorandum retracting some of the misguidance it had issued; bobbies on the beat were reminded that it wasn’t illegal to take photos. Seemingly, this was more a PR exercise or simply the rank and file didn’t get the memo. Harassment continued.

This situation has totally degraded. The level of trust between the photographic community and police authorities is at an all time low (more here and here). Granted, the Guardian is my sole source here, but it covers the issue so well.

Outside of Britain, incidents have occurred in Los Angeles and elsewhere in the US. Some might say there is a certain amount of baiting employed by some journalists’ tactics (Paul Lewis outside the Gherkin in London springs to mind), but they are merely testing the communication and enforceability of new directives immediately after they’ve been announced by police authorities (in Lewis’ case, directives from New Scotland Yard).

In 2010, I hope to see less harassment of photographers. But, if hassle does continue I hope (and expect) to see its continued reporting to keep the pressure on police chiefs and politicians … particularly in the UK.

And with that I have a site recommendation. Photography is Not a Crime is a good one-stop shop for the unfortunate new genre of photog/authority face-off stories.

The watchdog is compiled by Carlos Miller a Miami multimedia journalist arrested by Miami police after photographing them against their wishes. He goes into his case at length and I still don’t think it is resolved.

Regardless of his motives, Miller’s coverage is comprehensive. As a silo for moments of confrontation and antagonism, the Photography is Not a Crime blog can be a repeated depressing look at abuses of authority.

More than the individual stories – which warrant extended consideration in themselves – it is the cumulative weight and significance of collected incidents that makes Miller’s site a cultural mirror.

Photography is Not a Crime is a must-read for photographers and other media journalists.

I’ve never quite had a holiday like that before; the snowfall you always thought your parents were making up as they described the days when “real winters” hit.

Yesterday, Manchester airport availed itself and I got out. Arrived back in Seattle last night.

So I am back on the horse and I’ve got stuff to say (so does the horse).

During 1981, there were two hunger strikes – the culmination of a five-year protest during The Troubles by Irish republican prisoners in Northern Ireland.

Ten men died.

28 years ago today, 3rd October, the strikes were called to an official end.

In his book Prisongate (2005), David Ramsbotham, former Chief Inspector of Her Majesty’s Prison Service, quotes a young prison reformer, Winston Churchill.

Ramsbotham read Churchill’s words very early in his employment as Chief Inspector, and kept them close throughout his five year tenure. Ramsbotham understood the following quote as “the clearest possible condemnation of punitive, as opposed to rehabilitative, imprisonment.”

Churchill concluded the parliamentary debate:

We must not forget that when every material improvement has been effected in prisons, when the temperature has been rightly adjusted, when the proper food to maintain health and strength has been given, when the doctors, chaplains and prison visitors have come and gone, the convict stands deprived of everything that a free man calls life. We must not forget that all these improvements, which are sometimes salves to our consciences, do not change that position.

The mood and temper of the public in regard to the treatment of crime and criminals is one of the most unfailing tests of the civilisation of any country. A calm and dispassionate recognition of the rights of the accused against the state, and even of convicted criminals against the state, a constant heart-searching by all charged with the duty of punishment, a desire and eagerness to rehabilitate in the world of industry all those who have paid their dues in the hard coinage of punishment, tireless efforts towards the discovery of curative and regenerating processes, and an unfaltering faith that there is a treasure, if you can only find it, in the heart of every man these are the symbols which in the treatment of crime and criminals mark and measure the stored-up strength of a nation, and are the sign and proof of the living virtue in it.

House of Commons speech, given as Home Secretary, July 20, 1910

Note: Often Churchill’s House of Commons speech, July 20, 1910 is quoted without this first paragraph. Ramsbotham plumped for the expanded version.

Prisongate is a riveting book in which Ramsbotham details his observations, strategies, inspections and concern within a broken UK prison system. The London Review of Books said “Prisongate will make uncomfortable reading for ministers. It is a vivid and at times idiosyncratic account expressive in equal measure of personal frustration and moral outrage.”

Coverage of aging prison populations will receive more column inches, online commentary, pixels and pingbacks in the coming years. Just as social security needs overhaul in the US and the pension age is to be raised in the UK, so too new means of fiscal policy are needed to cater for the elderly behind bars … on both sides of the pond.

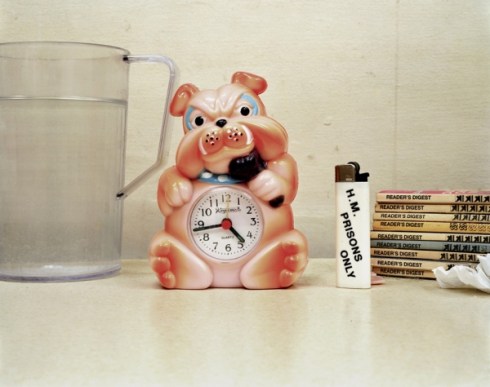

Edmund Clark’s Still Life: Killing Time is a quiet meditation on the slowness, the fabric and the accoutrements of prison life for elderly inmates. It was two years in the making. This was a hard project to track down. It seems all of Edmund Clark’s promotion is done by others; by publishers, journos, gallerists and supporters. Clark has no website. Clark is as inconspicuous as his subjects.

Clark doesn’t do the commentary for the Guardian‘s Audio Slideshow (MUST SEE). In his absence, Erwin James does a great job of whispering the tragic, hard realities of the prison environment. I include and italicise Erwin’s comments below Clark’s photographs.

“It saddens me when I see these pictures, these tokens of disablement, the accoutrements of disability; a chair lift, a walking stick, a walking frame. I think that is when I struggle with the idea that these people should be in prison. If someone is demonstrably infirm, demonstrably not functioning well through age or ill health, a prison environment (which this clearly is) is not the appropriate environment.”

It’s worth noting some background to the series. Elderly prison populations only recently became serious noticeable enough for HM Prison Service to trial different modes of containment. The E-Wing of Kingston Prison, Portsmouth was the first experiment. In 2007, upon publication of the book, Erwin James explained;

The answer was Kingston’s E wing. For eight years, this was home to up to 25 elderly men serving life for murder, rape, child sex offences and other offences of violence. The men were aged from their late 50s to over 80. Many had been in prison for more than 10 years, and several for stretches of 30 years or more. E wing as a special facility for elderly prisoners no longer exists. The only other wing dedicated to infirm and disabled prisoners now is in Norwich prison, Norfolk.

“I think cell bars are a tough one. They offer a difficult vista. When you look through cell bars you are aware that the outside doesn’t belong to you. You’re disengaged. And when you see cell bars with a bit of colour like that – the flower and the card – it’s a bit incongruous. These old guys are still humans.”

But for James, as for myself, and particularly for Clark, this is not about sympathy or compassion for the convicted criminal. It has already been stated that these men are serious criminals. There surely must come a point though when an old man is not the physical threat he once was. Simon Norfolk – a photographer I personally consider one of Britain’s best – wrote for the foreword;

” … why are there bars on the window of a man who can’t walk without a frame. What kind of escape plan can be hatched by a man who can’t remember how to go to the toilet.”

“This picture for me epitomizes the absurdity, and moments of madness the prison system can have. We are keeping someone in prison, who has dementia. They have basic instruction about how to go to the toilet. If there were ever a case for somebody who needs not to be in prison, it would be for that person.”

The only statement I can find directly from Clark, the photographer, is worth meditation.

What you can see in the pictures is to what extent they are engaged with their routine, and on top of their regime and what sort of engagement they have with time. One man, who wore a long grey beard, coped with the passage of time, as far as I could see, by disengaging with it completely. He spent most of his time sitting in his chair … He just sat and disappeared within himself. After about a year I could go and talk to him, and this man was clever, he’d been a captain in the merchant navy and had sailed around the world. I asked him once what was the best place he’d been to and he lifted his head and said, ‘Sao Paulo, I loved Brazil …’ And then suddenly this life came out, his life was all there, hidden away. The bulldog clock on the book cover belonged to him, it was one of his prized possessions.

Apparently, Clark created this body of work spurred by reports from the USA about mandatory sentencing under “Three Strikes Laws” and the consequent swelling of America’s prison population. Clark engaged with Britain’s aging prison population in direct response to demographic disasters in American penal policy. Clark elaborates;

People subjected to it [Three Strikes Law] were swelling the ranks of the prison population, with the result that many men sentenced when young would spend the rest of their lives incarcerated. I wondered what the response in the UK was to those incarcerated for many years – the life prisoners, or ‘lifers’, who face an old age and growing infirmity in an institutional environment still ruled by the survival of the fittest.

Clark made his point by seeking out the UK’s first specialised prison facility for aged prisoners and then produced a body of work that is distinctly British. Photographs of Bond posters, a (British?) Bulldog, Red-top clippings of Diana & the Queen, and framed artwork of common birds to British gardens & allotments; these are not obvious clues to a global appreciation of prison culture. I conclude, Clark thinks globally, acts locally.

“If you are young and strong prison is manageable on the whole. If you feel weak or infirm or poorly it is a harder place to be and these photographs epitomize the frailty factor, the danger of getting old in prison or being old in prison … My feeling about prison is that it is not a place for old people. Prison is one environment for everybody regardless of your circumstances and so what happens is your survival depends on luck and natural resources. And if you’re old you’re not gonna have as much luck as the younger guys.”

“There’s a lot of people in the system who know that prison is not a place for old, infirm, disabled people. And its not. I’m not saying that they shouldn’t be separated from society, but I am talking about prison as we know it. The common interpretation of prison is landings, wings, cells, prison officers, dogs, security; that whole encapsulation of captivity. If you are infirm there needs to be another place. We are giving extra punishment to the weak people.”

“There is an argument for separating the old folks from the main prison wing and that is what happened here. It was an experiment. E-Wing. The danger for me is that is becomes a place … you know, they talked of the fetid atmosphere; smelly and hot. The smell of old people. As a society we don’t have a lot of respect for old people.”

Clark’s unambiguous images of mobile aids and instructions for the senile are a clear call for change. His studies of prized-possessions and personal ordering of objects play on emotional responses to depicted vulnerabilities; Clark’s works conspire as a whole (43 images in total) to shape a convincing argument that we should all care about how our prison system accommodates different demographics. The elderly demographic is only growing, only advancing … with time.

As James’ words have served me so well throughout this article I shall close with his take on public opinion.

“I am pleased society is taking this on, because prison is a robust and hostile environment, and in fact the authorities refer to all prisons as hostile environments. That’s how they’re officially termed. That’s not because everyone who goes there are dangerous, but I think prison brings out the worst in a lot of people. It can bring out the best, but often it brings out the worst. And that’s not to say they are bad characters, it’s because people in prison are defensive and they are defensive because they are frightened.”

__________________________________________________________

All images copyright of Edmund Clark.

Still Life: Killing Time, by Edmund Clark, is published by Dewi Lewis, and avaiable at PhotoEye

LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM - 15.06.08. A Metropolitan Police Forward Intelligence Team (FIT) photographer films and photographs journalists as police and protesters clash during a demonstration against U.S President George W Bush in Parliament Square, Westminster on Sunday 15 June 2008, London, England. Protesters had been banned by the Metropolitan Police from demonstrating outside 10 Downing Street to protest against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. (c) Marc Vallée, 2008. http://www.marcvallee.co.uk

After reading this phenomenal post by Jamblichus about state surveillance and electorate apathy/powerlessness in the UK, I was compelled to post the above image.

I know for two posts now in as many days I have diverged from “photography in sites of incarceration”, but this topic keeps throwing up unanswered questions.

Forward Intelligence Teams , introduced in 1996, are now central to British policing of all public crowd events. F.I.T.s don’t try to hide. They are highly visible and operate use facial recognition technology to add folk on camera to a central database.

Jamblichus raises a really important question about this. What is the nature of this database? We should all be asking these questions: Under who’s authority is the database maintained. Which government departments have access to it?

Local councils in Britain have used anti-terrorism legislation to spy on its citizens for minor infractions. What is to stop similar abuse with regard this database? The UK has built a police state infrastructure and no-one is immune to its effects should the cameras and mics be pointed their way.

Is the British Press “free” in all definitions of the term? I think not.

I am probably in the database due to my interest in a seal-hunting protest outside the Canadian Embassy of London last year. I went over to have a peek and a natter, mainly because I was shocked that anyone would want to picket Canada! When I turned to continue on my way, I had two long-range lens pointing at me.

Jamblichus points us to The Journalist which describes the Met’s purposeful surveillance of the press;

Police tactics seem to be becoming more menacing. Photographers have complained that the Metropolitan Police’s Forward Intelligence Team (FIT) — set up to target public disorder and anti-social behaviour by having high-visibility police officers use camera and video footage to gather intelligence — has started surveillance of press-card carrying journalists. They say that images of them are given a four-figure “photographic reference number” and held on a database.

I’d really like to know when they’ll need 5 digits or more!…. While we wait on that you can look over the Flickr group FITWatch.