You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

THE DEMISE OF “CANADA’S ALCATRAZ”

In late 2013, and after 178 years in operation, Kingston Penitentiary in Canada closed. Located on the shores of Lake Ontario, the maximum security lock-up was one of the oldest operating prisons in the world and was considered “Canada’s Alcatraz.”

Geoffrey James photographed inside Kingston during its final year in operation and in the immediate aftermath of its closure. His book Inside Kingston Penitentiary (Black Dog Publishing) was recently published

The transitional moment in which the prison operated and James photographed makes for prison photography study unlike anything I’ve come across before. James uses both B&W and color to image the architecture, daily activities, cells, common spaces, staff and prisoners.

The transitional moment in which the prison operated and James photographed makes for prison photography study unlike anything I’ve come across before. James uses both B&W and color to image the architecture, daily activities, cells, common spaces, staff and prisoners.

It’s not apparent if the spaces in James’ photographs are lived in or not. Are we seeing an institution in wind-down, abandonment, stasis or half-use? In truth, all of these things, and the effect we are left with is that prison environments are wholly unnatural — people aren’t supposed to live or work in cages. And yet, a collision of behaviours, laws and controls has resulted in the construction of a man-made space to confine. James’ focus on Kingston’s 19th Century architecture and modern-day graffiti remind us of that.

I selected my favourite images from the 192-pages of Inside Kingston Penitentiary to accompany this conversation with Geoffrey James.

Scroll down for out Q&A.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Tell us about the prison.

Geoffrey James (GJ): Kingston Penitentiary (KP) had never really been documented in its 178-year history, except for press photographs of the destruction following a major riot in 1971.

The fact that it was closing gave me an opportunity to make the case for a historical document, with a university publication and exhibition. Fortunately, the warden and commissioner both realized that the day KP closed, it would become a different animal — a ruin, more or less, or a place of dark nostalgia. Eventually, approval for my project came from the Privy Council, the innermost sanctum of the government. Canada’s Corrections Service is famously closed and hermetic and, in general, prisons are the unknown element of the criminal justice system.

GJ: I have always had a curiosity about prisons, and KP is the most mysterious place of all — older than Canada, visited by Dickens, and notoriously tough. I went in without a huge amount of prior knowledge. From the responses I have had, I think a lot of people share my surprise about what I found. On one level the prison is impressive — it was built in the period of Late Georgian architecture, when there seemed to be no bad building.

GJ: Kingston was built by the prisoners, who first had to quarry the limestone. Its architectural language is highly symbolic, designed to impress and intimidate, as well as to hide what it is going on in side — no wire fences, but huge walls and a forbidding entrance.

PP: What is the prison system like in Canada?

GJ: The U.S. is a complete outlier among industrialized nations in the number of people it incarcerates. As Canada is next door, the perception is that we have a more benign system, which to some extent might be true. That said, it is clear that under the current government, prison policy is becoming noticeably more punitive in its intentions. We have had minimum mandatory sentencing laws, which surprisingly brought a response from U.S. law enforcement experts and prosecutors (and even conservative senators) saying this was ill-advised. Parole rules have been tightened and vocational training has been dropped in favor of cognitive behavior modification courses.

GJ: Even the $5.80/day that a prisoner can earn by working in the prison has been subjected to a 30-percent claw-back. At a time of falling crime rates, there has been a flurry of prison-building. There is an emphasis on “victims rights” which tend to concentrate on retribution and punishment. There is less emphasis in trying to prepare prisoners for their release. For the first time that I can remember, prison policy has become very much a partisan issue in parliament.

PP: How do Canadians think about prisons, officers and prisoners?

GJ: One of of the chaplains at KP said to me that Canadians don’t know much about what happens in prisons, and don’t care to know, which just about sums it up. There are the people who join the John Howard Society and work actively to try to improve conditions in prisons, as well as help prisoners on their release. There are the readers of the tabloid press, which often tries to paint prisons as holiday camps or “Club Feds.” In between, there is the majority of the population that tends not to pay too much heed, unless something horrific catches their attention.

PP: What sort of thing captures attention?

GJ: In Canada, we had not long ago, when a young woman named Ashley Smith ended her life while being watched on video by guards who had been ordered not to intervene, because she was always “acting out.” One of the things that some people learned from this was the widespread use of solitary confinement in Canada, though here it goes by the euphemism “administrative segregation.”

PP: What did you want to achieve with your work and the book?

GJ: I would hope that people looking at my book might be disabused of the notion that a maximum security is an easy place to be. For me, the most surprising thing were the words and images that the prisoners left on their walls, messages of anger, despair, regret and sometime also of wisdom and humor. People tell me they have been moved by these images.

PP: There’s evidence of staff in your photographs. That might sound strangely obvious but in America it is very rare that prison staff want to appear before the camera. Was that just part of your approach to capture as many angles of the prison and its people?

GJ: I tried to photograph as many aspects of prison life as I could. I was given remarkable latitude, and was always accompanied by a corrections officer. The attitude of the staff varied, as did that of the prisoners. There was sometimes a certain wariness about my presence, but I also met some outstanding and open officers.

GJ: The one requirement of the project was that I had to get a written release for every person depicted in the book. I think it significant that there was only one refusal among staff and prisoners. Not a single prisoner objected.

PP: What did the prisoners think of you and your camera?

GJ: Prisoners have a total sense of their own environment and know when there is a new species around. I found that prisoners — like the corrections officers — tend to be different on their own than when in groups. I had a difficult moment on the toughest range (or cell block) of the prison, where the prisoners had just been given a collective punishment, and decided to get back through me. Mostly, though, I took one person at a time, and learned some surprising things. I had the easiest relationship with the native prisoners, who have their own space for work and ceremonies, and who were an interesting group. They were lucky in that they had access to elders and could learn things about their heritage that they might not have had growing up.

PP: Do you have a political angle with these photographs?

GJ: It is a mistake to adopt an a priori “political” position. It is more effective to let the pictures tell the story without any rhetoric from me, although the book has a rather intricate structure that tells its own story. Or the story I wanted it to tell. I took some pains not to sensationalize the subject — I dialed back a little on the darkness that comes off those walls.

PP: You photographed Kingston Penitentiary as it closed down. Visually, I’d say there is an element of elegy. Was this intentional?

GJ: I am not sure whether the pictures are elegiac. I attempted to keep everything straightforward, neither dramatizing nor trying to make things overly emotional. But the truth is that the place has its own very strong aura. I visited the much newer maximum-security prison that many prisoners were sent to, and found it much scarier — cramped and sterile and so efficient that contact between staff and prisoners is minimized. A lot of the guards were very attached to the place. There was even one well-known prisoner who died before I started shooting who refused to leave for a lower-security institution because he considered it home. The staff refer to this as “nesting” and there seems to be a deliberate attempt not to make things comfortable in any way.

PP: Are there any particular aspects of history of Kingston Penitentiary, of which viewers should be aware?

GJ: When I researched its history, I was staggered to learn how early the problems of the institution started. Only 13 years after it opened, and a few years after Charles Dickens visited it (and found it very well administered), there was a commission of inquiry into the terrible regime of public flogging. KP had a long, troubled history.

In its closing months, there was very little in the way of rehabilitation, other than programs designed to modify cognitive behavior — programs for sexual offenders and those who had committed family violence, for example. It was interesting to me that in the 50s, the prison had its own band and on summer nights broadcast a variety show throughout the province. Now, it is all PlayStations, TV’s and boom boxes. The term that I heard over and over again from the officers was warehousing. Which pretty much sums it up.

PP: Thanks, Geoffrey.

GJ: Thank you, Pete.

All images: Geoffrey James.

I’ve said before that Angola prison is probably the most photographed prison in the nation. Damon Winter, Bettina Hansen, Darryl Richardson, Tim McKukla, Sarah Stolfa, Adam Shemper, Lori Waselchuk, Deborah Luster, Serge Levy, Frank McMains and thousands more. Even I’ve had a go!

Well, now add Giles Clarke to that list . He was down there at the end of 2013. A small edit of the pictures then appeared in Vice.

This is the second in an ongoing occasional series I have going with Clarke in which we chat about the whys and hows he’s going to prisons … which he is doing more frequently these days.

Remember, while all this palaver occurs in public-accessed areas, Albert Woodfox — the single member of the Angola 3 still incarcerated — awaits potential release on bail and a third trial. All this, in spite of the State of Louisiana’s case against him being largely discredited. As we’ll learn from Clarke, Louisiana has a strange definition of justice.

All images: Giles Clarke/Getty Images Reportage.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Prison Photography (PP): Why were you in Louisiana?

Giles Clarke (GC): I originally went down to the area to explore the toxic industrial corridor that runs from Baton Rouge south, along the banks of the Mississippi River, to New Orleans. The area is otherwise known as “Cancer Alley.” While researching that horrible story, I read in a local paper that Angola Prison would be holding its Prison Rodeo. It seemed like a good thing to do on a Sunday in the Deep South.

PP: Now, c’mon Giles, everybody and his mother has photographed the Angola Prison Rodeo. Why did you want to shoot it?

GC: A couple of years ago, I had made a short commercial film for ‘SuperDuty’ Ford Trucks, which featured about ten 1800lb bulls and some rather small Midwestern bull-riders. Seeing those bulls REALLY close-up left a deep impression. The guys who rode them were pros but they often got hurt. When I read the ad for the Angola Prison Rodeo, my thought was ‘How the hell are a load of prisoners going to deal with these huge animals?’ and secondly, ‘Why the hell are the prison letting them do it?’

Then, of course, there is the legacy of Angola. It just so happened that Herman Wallace — one of the Angola 3 — had died only 2 weeks before the rodeo. I attended his funeral in New Orleans which was held the day before the rodeo. It was a very moving occasion. If you know the story of Herman Wallace, then chances are you want ask some questions — which is what I did when I got into Angola the very next day.

PP: Was there anything specifically different you wanted to do at the Rodeo, or Angola generally? What did you want to achieve with your photographs?

GC: Most of the prison media officials were about as unhelpful as they could be. Yes, they were courteous and let me talk to the prisoners before, but when it came to the actual event, they kept us well away from the arena. We photographers were penned high-up in the nosebleed seats. Almost the whole rest of the audience was closer. It was blindingly obvious that they didn’t want to show the reality and the gore.

Whenever we asked about injuries we were fobbed off. That was a shame. Fact is, it’s brutal and it’s not pretty when things go wrong. Which they do a lot.

PP: The Angola Prison Rodeo looks pretty gladiatorial, but I’ve heard arguments to say it’s good for the prisoners — prize money, selling arts, meeting friends and family, glory and honor. What is your reading of the event?

GC: I was really skeptical to begin with but having talked to many of the prisoners who were involved in the event, I soon realized that this event was something that they really looked forward to. There was plenty of money at stake. If you pluck the puck from the bull’s nose, you win $500! Thats a lot of cash on the inside. Of course, the glory. If you win the rodeo you get to wear ‘Angola Prison Rodeo’ belt buckle.

At the end of the day, its a big money-making exercise that involves the prisoners. They make the products, sell the tickets for rodeo and take home about 10% of those earnings. The warden says this money goes back into rehab programs. If that’s really the case, then its a good thing.

PP: Who were weirder? The prisoners, the staff or the public?

GC: It’s hard to focus that question. I’m from the UK and to be honest, I find all this stuff fucking weird! I find the entire Louisiana justice system almost laughable … except for many its far from laughable. In Angola, there are over 5,000 men are held for life with no chance of parole — they’ll never ever leave. They talk about rehabilitation, but for what? So you don’t get sent to the punishment wing for your entire life? It’s all so messed up but they seem to think they are on the right path.

You gotta remember also that 2,000 staff family members live on the grounds of Angola. It’s work that is welcomed and promoted. Incarceration for many is a profitable business that needs to be continually fed. It’s an ugly beast whichever you look at it. Guess it’s better that Angola 40 years ago, when conditions were mostly described as squalid and medieval.

PP: When you spend time in Louisiana, does Angola Prison start to make sense?

GC: Well, as much as any prison can make sense. Mass-murderers and serial killers need to be locked and probably sent down for the rest of their lives, but in the USA, and especially in Louisiana, they want to lock you up as soon as they legally can often for crimes that do not comprehensibly meet the sentence.

I am very cynical toward the American justice system. It can work for you, if you have the money. Most don’t, so down they go for, usually for as long as they can *legally* send you down. Clearly, it’s better if you ain’t black. The prison business is big bucks for so many that it’s now sadly an accepted part of American society. For Angola, its a dead end. It’s depressing and fucked up. What else can I say?

PP: And so does the rodeo make sense?

GC: The rodeo was actually thought up by Jack Favor, a man who was framed for two murders and wrongly convicted for life in Angola. He was eventually released in 1974. As a former rodeo rider himself, he is the man who instilled the original self-discipline mantra into rodeo riders in Angola when it opened to the public in 1967. The whole idea came from a wrongly convicted prisoner. That was interesting to me. For the prisoners here now, it is an honour to be picked for the twice annual rodeo. And a chance to gain some self-worth and respect … and cash.

PP: Tell us about your relationships with the prison administrators.

GC: I don’t have a lot to say about them, other than they have unions, want full jails and probably don’t really give a fuck about most of the people they oversee.

They have families and need a job. I’m sure they are decent enough people but I can’t imagine that it’s much about helping people. I’m not sure one grows up saying “You know what, one day I want to work in a prison.” Maybe some do? Either way, the prison industry, like the military, is pretty much one big lie that we all tow along with. “It’s for the sake of safety and security.” Bollocks. It’s big business full stop.

PP: Did you meet Warden Burl Cain?

GC: I did. And I liked him. I found him refreshing and honest.

PP: He’s a bit of a media-celeb at this point and he divides opinion.

GC: While other journalists at the event asked him fairly straightforward rodeo related questions, we asked him some pretty tough things in regard to conditions, the Angola 3 and Herman Wallace. Cain answered them all directly.

Cain can be credited for turning Angola into the place of relative calm that it appears to be today. That had to happen. The dark legacy of Angola was something he wanted to wash away. His rehabilitation programs which give the prisoners work and more importantly, self worth, cannot be underestimated in prison reform. In many ways, he’s just the gatekeeper. He has to keep a clean and busy prison. I was impressed by him and hope others might model prisons after him. It was Burl that made sure that I was allowed back into the facility the next day for a private tour. It would not have happened without him. I thank him for that.

PP: Did you meet memorable prisoners, who said things to you that you maybe cannot say in your pictures?

GC: I met Bryce, (above) prisoner #582440, both at the rodeo and the following day inside his jail wing. At 26-years-old and serving life with no chance of parole, Bryce had been at Angola for 3 years, and said it’s the best prison he’s been in. He was locked up for second-degree murder, but is trying to fight the charges.

“It was a bar-fight, someone threatened my brother, I pulled a gun, it dropped and fired. That stray bullet killed a man,” he said.

The original charge was manslaughter, but, as Bryce said, “This is Louisiana.” I asked Bryce how he survives knowing he’ll never return to the outside world.

“How do I keep going? It’s all about respect in here. As long as I respect the next man and don’t show weakness then it’s all fine. The rodeo is something I look forward to all year so I behave ‘cause this is a real privilege.”

PP: What do you want folks to take away from your Angola photos?

GC: Why do we have 5% of the worlds population but 25% of the world’s prisoner population? Are we really doing this right?

In the eyes of those who run the current incarceration system, things are going just fine. But with the decriminalizing of certain low-level drug offenders and minor repeat offenders, one must assume that the authorities are also nervous about keeping these ridiculous occupancy levels so high. Private prisons are a huge worry. As are the new immigration centers that are bursting at the seams. From the outside, the U.S. seems to encourage mass-incarceration and most members of the public are still sort of okay with that. It’s fucked up.

One hopes that pictures can affect change but the reality is that no-one in authority really wants to affect change or be the focus. Many like it all the way it is — it keeps the dollars coming in after all.

PP: Thanks Giles. Until our next collaboration …

GC: Thank you, Pete.

All images: Giles Clarke/Getty Images Reportage.

Prison Obscura is currently at the mid-point of its New York showing at Parsons The New School of Design. At this moment, I wanted to share with you a few installation shots made by Marc Tatti for Parsons.

I also took the opportunity to re-issue the Prison Obscura catalogue essay (originally published by Haverford College) on Medium. Read Can Photographs of Prisons Improve the Lives of Prisoners?

I have hi-res images of all artworks and installation shots. Should you need any, drop me a line.

Enjoy the weekend!

All images: Marc Tatti.

Every Friday Evening, in New York City, Women and Children Board Buses Headed for Upstate Prisons

Photographer Jacobia Dahm Rode Too and Documented, Through the Night, the Distances Families Will Go to See Their Incarcerated Loved Ones

_____________________

There are various ways to depict the family ties that are put under intense strain when a loved one is imprisoned. Photographers have focused on sibling love; artists have focused on family portraits, and documentarians have tracked the impact of mass incarceration across multiple generations. Often, the daily trials of family with loved ones inside are invisible, unphotographable, psychological and persistent—they are open ended and not really very easy to visualise.

One of the many strengths of Jacobia Dahm’s project In Transit: The Prison Buses is that it very literally describes a time (every weekend), a duration (8 or 10 hour bus ride), a beginning and an end, and a purpose (to get inside a prison visiting room). In Transit: The Prison Buses is a literal example of a photographer taking us there. Dahm took six weekend trips between February and May 2014.

Dahm’s method is so simple it is surprising no other documentary photographer (I can think of) has told the same story this way. Dahm told me recently, that since the New York Times featured In Transit: The Prison Buses in November 2014, the interest and gratitude has been non-stop. I echo those sentiments of appreciation. Dahm describes a poignant set of circumstances with utmost respect. It is not easy to travel great distances at relatively large cost repeatedly, but families do. As a result, they take care of the emotional health of their loved ones — who, don’t forget are our prisoners — and society is a safer place because of it.

“Honestly, I don’t know why they place them so far away,” says one of Dahm’s subjects in an accompanying short film.

The women on these buses—and they are mostly women—are heroes.

I wanted to ask Jacobia how she went about finding the story and photographing the project.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Prison Photography (PP): Where did the idea come from?

Jacobia Dahm (JD): In the fall of 2013, I began studying Documentary Photography at the International Center of Photography in New York. When the time came to choose a long-term project, I realized I had been captivated for a long time by the criminal justice system here in the U.S., where I had lived for the past decade. Frequently the severity of the sentences did not seem to make any sense, and the verdicts seemed to lack compassion and an understanding of the structural disadvantages that poor people — who make up the majority of prisoners— face. In short, sentencing did not seem to take human nature into account.

My sense of justice was disturbed by all of this. I was shaken when Trayvon Martin was killed and his killer walked free. Or when shortly after, Marissa Alexander, a woman who had just given birth, was given a 20-year sentence for sending a warning shot into the roof of the garage when cornered by her former abusive partner. Her sentence has since been reduced dramatically. But it’s complex: Where does a society’s urge to punish rather than help and rehabilitate come from? In both cases there was a loud public outcry. What’s remarkable is that there are frequent public outcries against the US justice system, because the system simply does not feel just. So I decided to do some work in this area.

JD: But how do you even begin to photograph injustice?

My original plan was to take on one of the most worrisome aspects of US criminal justice: I wanted to photograph the families of people who were incarcerated for life without parole for non-violent offenses. But New York State does not incarcerate in that category and, as I had classes to attend, travel to further locations would have meant trickier access and less time with the subjects.

In conversation with one of my teachers Andrew Lichtenstein, who had done a good amount of work on prisons, he mentioned the weekend buses that take visitors to the prisons upstate. And once I had that image in my head — of a child on these buses that ride all night to the farthest points of New York State to see their incarcerated parent — I wanted to go and find that image.

PP: How much preparation did you need to do? Or did you just turn up to the terminus?

JD: I researched the bus companies beforehand, some of them are not easy to find or call. And I had to find out which company went where. I also looked into the surroundings of each prison beforehand. I knew I would not be able to go into prison and knew most of them are in the middle of nowhere, so I had to make sure — especially since it was in the midst of freezing winter — that I would be within walking distance of some sort of town that had a cafe.

The first time I went upstate, it was on a private minivan. I had just finished reading Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s amazing non-fiction book, Random Family that narrated life over a decade in the 1980s and 90s in the South Bronx. The characters in the book travel with a company called “Prison Gap” which is one of the oldest companies running visitor transportation in New York City, and so I felt they were the real deal and decided to use them on my first trip upstate.

It was a freezing February night in 2014 and we gathered in a Citibank branch south of Columbus Circle for two hours before the minivans appeared. Many people came in to use the ATMs and some looked at us wonderingly, but no-one would have known that these people were about to visit prisons. What they would have seen is a mostly African-American crowd, mostly women, waiting for something.

PP: I see Attica in your photos, did you just photo one route or many?

JD: The bus I ended up focusing on — because riding on the same bus would allow me to get to know passengers better — went to six different prisons in the Northwest of New York State: Groveland, Livingston, Attica, Wyoming, Albion and Orleans. Most buses and mini vans ride to a number of prisons, that way they always have a full bus because they serve a wider demographic.

I wanted to be on a bus that went to Albion, the largest women’s prison in NY State, because my assumption was, that female prisoners get more visits from their children, simply because the bond is almost always the most crucial one. But I was wrong, because as it turns out, women have fewer visitors, and for a number of reasons: Women tend to act as the social glue and make sure visits happen. And so when they’re the ones who are incarcerated, not everyone around them takes over or can take over the same way. Some dads are absent and if the children are raised by the grandmother, that trip will be very difficult to make for an elderly person.

PP: What were the reactions of the families to your presence, and to your camera?

JD: The time I traveled upstate I was squeezed into the back of a white mini van, the only white person traveling up and the only one with a camera strapped around her neck. We drove all night and barely talked. It felt otherworldly thinking we are now driving to the Canadian border, but I forced myself to take at least a few pictures through the frozen window and of hands etc. Later the next morning we were moved to a larger bus and that bus was the one I rode on for the next five rides between February and May.

JD: The first one or two times I took the trip, I did not take many pictures on the bus and I photographed the towns instead. I could quickly tell there was a sense of shame involved in having family in prison, and people where uncomfortable being photographed, which I understand. People had to get used to me first an understand what I was doing. So I did what you do when you are in that situation: I introduced myself to people, I took some pictures and brought them a print next time.

Once they had seen me on the bus more than once they were starting to be intrigued. I also told them that I too was a parent and could not imagine having to bring my children on such a long and difficult journey, and that I was sorry this was the case for them. I think it was rare for many of these women to encounter any kind of compassion from others, and it might have helped them to open up to me.

PP: You describe the journeys as emotional, tiresome, grueling.

JD: You’re on the bus all night without getting much sleep. The expectations of the visits can be tense, because the mood of your entire relationship for the next week is depending on a few hours. But the journey has also been expensive and most likely exhausted all your funds for the week. During the visit you will be watched closely by the correctional officers, some of them might be rude to you. And if you bring your kids that aspect might be particularly difficult because you’re in no position to stand your ground.

You worry and hope your kids sleep well because you want them to be in good shape for the visit. I knew a grandmother who slept on the floor so her grandson could get the sleep he needed.

JD: Another one of the moms I knew was not allowed to bring her three kids to Attica because Attica only allows for three people to visit. The child that was left at home with a babysitter or family member was upset and that puts stress on the entire family.

PP: Why are New York State’s prison so far upstate?

JD: New York has around 70 state prisons, and many of them are in rural, post-industrial or post-agricultural areas. You could not get to some of these towns with public transport if you wanted to. The prisons have been economic favors to depressed rural areas that have little else to offer in terms of jobs, but not factored in is how these favors tear families apart and further widen the distance between children and their incarcerated parents.

PP: Do other states have similar geographic distances between communities and prisons?

JD: I am only beginning to understand what the system looks like in other states, but I believe people have to travel far in most states, as there seems to be no policy on the part of Departments of Corrections to place prisoners in proximity to their families.

In California for example, most prisoners at the Pelican Bay State Prison come from Los Angeles, and that prison is a 12-hour ride away. In Washington D.C. it seems a large part of the prisoners are placed federally, rather than within state, so the distances can be even larger. And with distance come increased travel costs that poorer families have a very hard time covering with regularity.

JD: Considering that family ties are crucial in maintaining mental health and key in helping the prisoners regain their footing when they are out, it is a cruel oversight not to place people closer to those that are part of the rehabilitation process. Statistics tell us that the majority or prisoners have minor children.

PP: What can photography achieve in the face of such a massive prison system?

JD: I think at the very least pictures of an experience we know nothing about can create awareness, and at best it can move people to develop a compassion that can move them to act. I think a photograph can give you a sense of how something feels. Seeing is a sense of knowing, and it’s easy not to care if you don’t know.

In the face of the U.S. incarceration system — a system that seems to be concealed from most people’s sight but at the same time permeates so many aspects of the American life and landscape—it feels particularly important to me that photography plays the role of a witness.

PP: How do you want your images to be understood?

JD: I think my images highlight a difficult journey that many people know nothing about.

The focus of the journey, and of my photographs, is on the people that connect the inside of a prison to the outside world: the families.

It might be that by seeing how an entire family’s life is altered people seeing those images and beginning to understand something about how incarceration affects not just the person on the inside, they are maybe capable of a compassion they don’t usually afford for prisoners themselves.

PP: How do you want your images to be used?

JD: It’s hard to say because I believe an artist’s intention has limits when it comes to how the work is used.

I want people to put themselves in the families’ shoes. I want these images to help people begin to imagine what the secondary effects of incarceration are and how they could be softened. 10 million children in the US have experienced parental incarceration at some point in their lives, and that is not a good start in life for a very large number of the most vulnerable population.

BIOGRAPHY

Jacobia Dahm (born Frankfurt, Germany) is a documentary storyteller and portrait photographer based in New York and Berlin. She graduated from the International Center of Photography in 2014, where she was a Lisette Model Scholar and received the Rita K. Hillman Award for Excellence. Dahm’s photography and video has been recognized with awards from Rangefinder and the International Photography Awards. Her work has been published by Makeshift Magazine, The New York Times, Shift Book, AIAP and Prison Photography. Her key interest is documenting issues of social justice.

8 June 2012: Crescent City, CA. California State Prison: Pelican Bay Prison. Examples of kites (messages) written by prisoners. These were discovered before they were smuggled out.

Too often since writing this post, I have lamented the dearth of images of solitary confinement. We have suffered as a society from not seeing. A few years back a change began. Solitary confinement became an anchor issue to the prison reform and abolition movements. Thanks largely to activist and journalist inquiry we’ve seen more and more images of solitary confinement emerge. However, news outlets still relying on video animation to tell stories, which would indicate images remain scarce and at a premium.

Robert Gumpert has just updated his website with photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison. Some are from the Secure Housing Unit (SHU) that has been the center of years of controversy and the locus of 3 hunger strikes since the summer of 2011. Other photographs are from the general population areas of the supermaximum security facility.

Click the “i” icon at the top right of Gumpert’s gallery to see caption info, so that you can be sure which wing of this brutal facility is in each photograph.

Despite seeing Gumpert regularly, I am still not aware of exactly how these images came about. I think Gumpert was on assignment but the publication didn’t, in the end, pull the trigger. Their loss is our gain. Gumpert provides 33 images. It’s a strange mix. I’d go as far to say stifled. Everything is eerily still under dank light. We encounter, at distance, a cuffed prisoner brought out for the camera. Gumpert’s captions indicate interviews took place, but there are no prisoners’ quotes. In a deprived environment it makes sense that Gumpert focuses on signs — they point toward the operations and attitudes more than a portrait of officer or prisoner does, I think.

The gallery opens with images from the SHU and then moves into the ‘Transition Housing Unit’ which is where prisoners who have signed up for the Step-Down Program are making their transition from assigned gang-status to return to the general population. Critics of the Step-Down Program say it is coercive and serves the prisons’ need more than the prisoners.

Note: It doesn’t matter how the prisoner identifies — if the prison authority has classed a prisoner as a gang member it is very difficult to shake the label. The Kafkaesque irreversibility of many CDCR assertions was what led to a growth in use of solitary in the California prisons.

8 June 2012: Crescent City, CA. California State Prison: Pelican Bay Prison. A SHU cell occupied by two prisoners. Cell is about 8×10 with no windows. Bunks are concrete with mattress roles. When rolled up the bunk serves at a seat and table.. Cones on the wall are home made speakers using ear-phones for the TV or radio. Speakers are not allowed.

I’ve picked out three images from Gumpert’s 33 that I think are instructive in different ways. While we may be amazed by the teeny writing of a prisoner in his kites (top) we should also be aware that these were shown to Gumpert to re-enforce the point that prisoners in solitary are incorrigible. The suggestion is that these words are a threat and we should be fearful. But we cannot know if we cannot read them fully. How good is your eyesight? Click the image to see it larger.

As for the “speakers” made of earphones and cardboards cylinders! Can those really amplify sound in any meaning full way?

And finally, to the image below. I thought the quotation marks in the church banner (below) were yet another case of poor prison signage grammar, but reading the caption and learning that the chapel caters for 47 faiths, makes “LORD’S” entirely applicable. Not a single lord but the widest, most ill-defined, catch-all version of a lord (higher presence/Yahweh/Gaia/Sheba/fog-spirit/Allah/fill-in-the-blank) in a prison that is all but god-forsaken.

See the full gallery.

8 June 2012: Crescent City, CA. California State Prison: Pelican Bay Prison. The religion room serving 47 different faiths and beliefs.

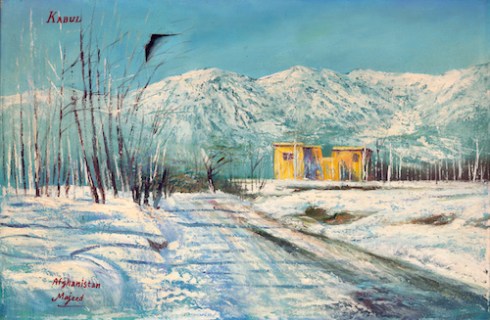

Edmund Clark is cheeky, thoughtful and a bit subversive in his critique of institutional power. During his 10 days embedded at Bagram Airbase in October 2013, he realised most people there don’t ever get outside its confines.

But Bagram has nice paintings of murals to provide an idealised Afghanistan.

My latest for WIRED, The 40,000 People on Bagram Air Base Haven’t Actually Seen Afghanistan I consider his latest body of work and book Mountains Of Majeed:

Clark documented the infrastructure needed to support a military base that covers 6 square miles and employs 40,000 people. He photographed everything from the mess halls and laundry to the sewage treatment system, but the colorful murals and paintings dotting the base most intrigued him. They depict an idyllic, romanticized vision of the local landscape and Hindu Kush, one free of war. The reality, of course, was much bleaker, with the distant peaks of the mountains beyond Bagram riddled with conflict and danger.

Read the piece in full.

G-LAW

Fight Hate With Love, a documentary film about Philadelphia-based artists and activist Michael Tabon (a.k.a. G-Law a.k.a. OG-Law) has been shortlisted for the Tim Hetherington Trust‘s inaugural Visionary Award.

The film made by Andrew Michael Ellis, director of photography at Mediastorm is about “one man’s journey to change the world and still be the guide his family needs him to be.”

The film looks inspiring, but as with any narrative arc, the protagonist faces challenges. It seems the stresses of Tabon’s art and activism upon his family is the emotive hook, Ellis is molding.

I met Tabon and his wife Gwen this time last year as he was embarking on his third self-imposed lock up in a self-built cell on the cold February streets of Philly. They did not display the tension as they do in Ellis’ trailer. Tabon was putting his un-prison cell together and Gwen was helping with supplies, PR, food & drink, and vocal support. It was clear they rely on one another to make work and to meet the silent, unending need for Tabon’s love-filled message.

Tabon’s manipulation of visual tropes is cunning and effective. He has reclaimed the cell, the orange jumpsuit and the shackles. He has jogged 10 miles a day for seven days around Philadelphia with a 40-foot banner reading FIGHT HATE WITH LOVE. He has walked with a ball-and-chain from Selma to Montgomery.

“Tabon has been caught in the revolving door of the prison system since he was sixteen years old. Incarceration became a way of life, seen as an inherited destiny for America’s young Black poor, until he had a revelation – that he could break the cycle of the womb-to-prison pipeline gripping marginalized communities across the country,” says Mediastorm.

It’s wonderful to see Tabon on the Mediastorm platform and Hetherington Trust’s radar. His unorthodox but unmissable approach to social change needs to go national.

Youtube trailer here. Follow Tabon on Twitter and on the web.

We hear often, from the extreme political right and left, that Washington D.C. is broken. People across the nation grumble about how the power-heeled mingle with elected representatives on Capitol Hill and achieve little for the everyman. Putting the efficacy of the political system aside, what about Washington D.C. as a city? What about D.C.’s governance and its ability to provide for its residents?

A look at Kike Arnal‘s series In The Shadows Of Power would tell us that D.C. is failing and it is the poor and disenfranchised it fails most. The series features photographs of youth locked in the city’s jail (above).

“Washington, D.C. is truly a world symbol in ways most people do not understand. It is my hope that the work in this book might expand that understanding,” says Arnal.

I visited D.C. last week and it felt good and weird. The video exhibit at the Hirschorn was amazing, the Reflecting Pool was drained and scummy, a new $400M Museum Of The Bible had just been announced, and the Ethiopian food was tremendous. But I got the feeling I was treading the visitors’ routes rather than the locals’ usual routes. I stayed in NoMa, which is a new acronymic fancy recently applied to the area North of Massachussetts Avenue.

[ Note: Acronyms are surefire evidence of realtor-orchestrated change — think SOMA, NoPa and TriBeCa. ]

NoMa is where the new headquarters of NPR are located. It’s undergoing massive change as Washington D.C. spiffs itself up in the blocks north of The Mall, Union Station and Congress. Historically though, it has been a poor area. No more. The poorest residents of D.C. are pushed around, from neighbourhood to neighbourhood. All the while, the D.C. metro area is the “centre of the free world.”

The economic downturn of 2008 barely touched D.C. With such a high proportion of government jobs, the capitol didn’t suffer in the same way cities reliant on industry and services did. As a result, migration into D.C. among the young and hungry picked up, and the renters market boomed. Areas that had, for the longest period, been home to lower economic classes changed wholesale. For example, vacant lots in the 14th Street area — which was devastated by 1968 riots in the wake of Martin Luther King’s assassination — were only developed in the last decade. And even then it was with Target, Starbucks and other chain name stores.

The area was left to waste until such a time it was useful for corporate/consumer interests.

Arnal talks about the body of work on C-Span here and Ralph Nader sings the praises of In The Shadow Of Power on Democracy Now! In that same program, Arnal talks about the photo of the coffeeshop (above).

In the Shadow of Power was sponsored by the Washington, DC, based Center for Study of Responsive Law which was founded by Ralph Nader in 1968. The Center has sponsored a wide variety of books, organizing projects, litigation and has hosted hundreds of conferences focusing on government and corporate accountability.

BIOGRAPHY

Kike Arnal is a Venezuelan photographer and documentary filmmaker based in New York City. His photographs have been featured in the New York Times, Life, and Newsweek, among others. His video, Yanomami Malaria, produced for the Discovery Channel, covered the spread of disease among populations of indigenous people in the northern Amazon. Follow Kike on Tumblr.