You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Rehabilitative’ category.

I wanted to trace the physical and psychic contours of the world of these young people to see what they might reveal. Juvies is not only a document, but also a query about perception. Do we know who these young people are and what we are doing to them?

Ara Oshagan

The Open Society Documentary Photography Project launches Moving Walls 17 exhibit today. Ara Oshagan, one of the seven award recipients, alerted me to the New York launch and his inclusion, Juvies: A Collaborative Portrait of Juvenile Offenders.

Juvies is collaborative because often his images are accompanied by the handwritten texts of incarcerated young people. Frequently the writings focus on emotional ties, problems with self esteem, the powerlessness against a system. It makes sense then that many of Oshagan’s photographs are visually-fractured, detached.

Compositions of door-frames, window reflections, outside corridors and gestures to action the other side of barriers describe very literally the immediate limitations these young people face daily. Oshagan’s work is not to politicise, but to describe (as best that is possible in the manipulating medium of photography.)

Oshagan explains, “I did not meet any angry or tattoo-ridden kids decked out in the clothes and accessories that could mark them as members of the city’s gang culture. Rather, I found a group of ordinary young men and women who had signed up for a video production class. When I spoke to them, they were deferential. For them, candy was the “contraband” article they had brought to class. Some of the kids were interested in photography and told me about how they strove to learn white balance. I listened to one of the kids play Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” on [a keyboard]. And somehow I had come full circle: I had played that exact same piece to my own son the night before. Suddenly, the distance between the inside and the outside seemed to vanish into thin air, a vast gulf turned into an imperceptible chimera.”

PHOTOGRAPHING INSIDE

Before accompanying filmmaker friend, Leslie Neale* into Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall, Oshagan wasn’t an activist or particularly interested in prison reform. Oshagan admits the exposure to the system and young lives within was disorienting. From Oshagan’s artist statement:

“I was in a privileged place that allowed the perceptions that existed in my head to be confronted by the realities I was witnessing in the closed and misunderstood world of incarceration. What I was seeing was also raising issues that would not give me peace.”

“I can understand why Mayra might get life in prison for shooting her girlfriend from point blank range. But how could a combination of relatively minor charges result in the same life sentence for Duc, an 18-year-old who, despite having no prior convictions, was convicted in a shooting crime that resulted in no injuries and in which he did not pull the trigger? And why did Peter – a 17-year-old piano prodigy and poet – get 12 years in adult prison for a first time assault and breaking and entering offense? Why is the justice system so harsh on kids who clearly have potential?”

PHOTOGRAPHING OUTSIDE

In addition to the walls, the guards, the other incarcerated people, the yards, the bunk beds, Oshagan also photographed families and communities left behind as well as the courts and victims. Sadly, I cannot present these images here but consider them essential in Oshagan’s “layered photographic narrative”.

These young people cannot be ignored. Our actions, just as theirs have ramifications both sides of the walls.

Two weeks ago the Supreme Court of the United States of America changed law, ruling life imprisonment without parole (LWOP) for a non-capital offense by a juvenile was to be removed from the books. Get past the fact that such harsh punishment was illogic and cruel and one soon arrives at the maddening circumstances of some of Oshagan’s subjects, Duc.

High school student Duc was arrested for driving a car from which a gun was shot. Although no one was injured, Duc was not a member of a gang, had no priors and was 16 years old, he received a sentence of 35 years to life

Again, to quote Oshagan, “Do we know who these young people are and what we are doing to them?”

* Oshagan did the B-Roll for Neale’s documentary film Juvies, whose own words about the juvenile detention system are worth taking in.

BIOGRAPHY

Born into a family of writers, Ara Oshagan studied literature and physics, but found his true passion in photography. A self-taught photographer, his work revolves around the intertwining themes of identity, community, and aftermath.

Aftermath is the main impetus for his first project, iwitness, which combines portraits of survivors of the Armenian genocide of 1915 with their oral histories. Issues of aftermath and identity also took Oshagan to the Nagorno-Karabakh region in the South Caucasus, where he documented and explored the post-war state of limbo experienced by Armenians in that mountainous and unrecognized region. This journey resulted in a project that won an award from the Santa Fe Project Competition in 2001, and will be published by powerHouse Books in 2010 as Father Land, a book featuring Oshagan’s photographs and an essay by his father.

Oshagan has also explored his identity as member of the Armenian diaspora community in Los Angeles. This project, Traces of Identity, was supported by the California Council for the Humanities and exhibited at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in 2004 and the Downey Museum of Art in 2005. Oshagan’s work is in the permanent collections of the Southeast Museum of Photography, the Downey Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art in Armenia.

MOVING WALLS 17

Also supported by the Open Society Documentary Photography Project are Jan Banning, Mari Bastashevski, Christian Holst, Lori Waselchuk & Saiful Huq Omi and The Chacipe Youth Photography Project.

Over two million individuals are behind bars in U.S. prisons, living in isolation from their families and their communities. Prison/Culture surveys the poetry, performance, painting, photography & installations that each investigate the culture of incarceration as an integral part of the American experience.

As eagerly as politicians and contractors have constructed prisons, so too activists and artists have built a resistance. Nowhere are these two forces pushing against one another as forcefully as in California. The book, Prison/Culture, compiles the documents of a two year collaboration between San Francisco State University, Intersection for the Arts (one of San Francisco’s oldest art non-profits) and prison artists & outside activists across the US.

Mark Dean Johnson’s essay summarises the visual/cultural history of incarceration; from Gericault’s institutionalized mentally ill subjects and his paintings of severed heads as protest against capital punishment, to Goya’s prison interiors of the inquisition; from Alexander Gardner’s portrait of Lincoln’s assassin Lewis Payne (1865), to Otto Hagel’s portrait of Tom Mooney (1936); and from Ben Shahn’s murals against indifference to the conditions of immigrant workers (1932) to the work of Andy Warhol and David Hammons in the modern era.

Johnson guides this lineage to the Bay Area, describing how Michel Foucault’s book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison became the conversation topic of Bay Area coffeehouses and classrooms (Foucault began lecturing at UC Berkeley in 1979). The swell of interest in Foucault’s structuralism coincided with a grassroots expansion of prison art in the early 1980s.

For text, the editors of Prison/Culture made two canny and provocative choices: Angela Y. Davis and Mike Davis (no relation).

THE TEXT

Firstly, in a 2005 interview, America’s most notorious prison abolitionist Angela Davis sets out – in her most accessible terms – how our prison industrial complex serves primarily as a tactical response to the inadequate or absent social programs following the end of slavery. Abolition was successful in that it redefined law, but it failed to truly develop alternative, democratic structures for racial equality. Powerful stuff, yet even newcomers to Davis’ argument won’t be as shocked as they may expect to be. She’s that good.

Next up, Mike Davis’ 1995 essay ‘Hell Factories in the Field’ is a bittersweet ‘I-told-you-so’-inclusion. Davis has made a specialty of dealing with – in stark academic prose – disaster scenarios, race-based antagonism and the environmental rape of recent Californian history. When Davis witnessed the mid-nineties expansion of the prison industrial complex (or as Ruth Gilmore Wilson terms it ‘The Golden Gulag’) he foresaw prisons’ economic band-aid utility for depressed towns; foresaw the mere displacement of violence; foresaw the assault on fragile family ties; foresaw the unconstitutional prison overcrowding and predicted the collective collapse of moral responsibility.

Davis’ article focused on the then new California State Prison, Calipatria – and not in a dry way. Paragraphs are devoted to recounting the installation of the world’s only birdproof, ecologically sensitive death fence following impromptu electrocutions of migrating wildfowl. The editors note, as of 2008, Calipatria’s facility design of 2,208 beds was 193% over-capacity with 4,272 inmates. Where birds saw an improvement in their lot, prisoners certainly did not, have not.

THE ART

Contributors include some well-known names – RIGO, (here on PP) Sandow Birk, Deborah Luster and Richard Kamler whose works address incarceration, criminal profiling, wrongful conviction, prison labor, and the death penalty. The book also includes poetry by Amiri Baraka, Ericka Huggins, Luis Rodriguez, Sesshu Foster and others but I shall not comment on these wordsmiths (their work is beyond my purview) other than to say they are talented and politically in the right place.

Special mention must go out for Deborah Luster’s One Big Self project (more here). In my personal opinion, it is the single most important photographic survey of any US prison. It is certainly the most longitudinal. Over a five year period, Luster visited the farm-fields, woodsheds, rodeos and national holiday & Halloween events throughout Louisiana’s prisons. She became a loved and recognized figure among the prison population; she estimates she gave away 25,000 portraits to inmates. Luster’s conclusion? Even mass photography struggles to communicate the vast numbers of men and women behind bars.

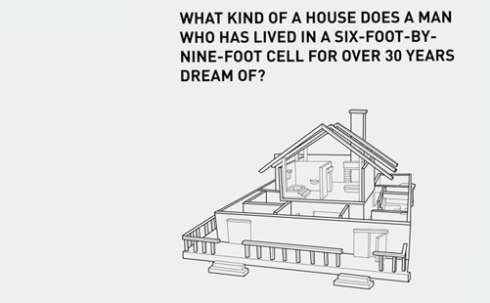

In 2003, artist Jackie Sumell collaborated with Herman Joshua Wallace (one of the Angola 3) on the design of his “Dream House”. The project The House That Herman Built is heartbreaking and bittersweet.

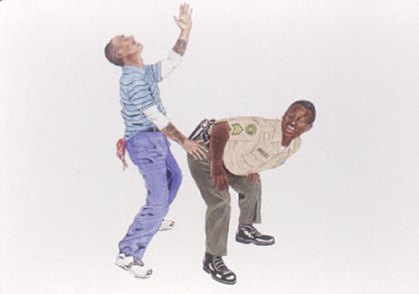

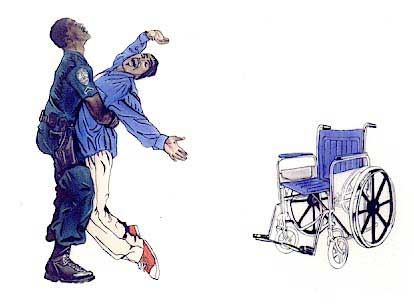

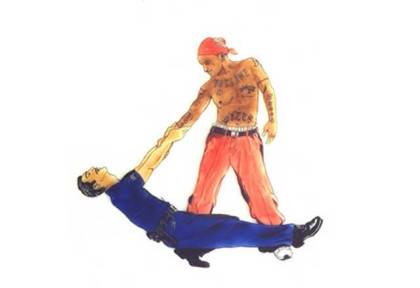

Alex Donis employs cunning and cutting humour for his series WAR. He sketches criminal “types” with figures of authority (policemen, prison guards) mid-dance, often bumping and grinding. He even conjures a kiss between Crips and Bloods gang members.

Also unexpected is the visual testimony of condemned mens’ last requested meals. For The Last Supper, Julie Green painstakingly painted porcelain plates with the last meals of nearly 400 executed men. Grayson Perry won the Turner Prize a few years ago, in large part due to his vases of abuse, bigotry and social ills. This clever use of regent materials has also been adopted by Penny Byrne for her Guantanamo Bay Souvenirs which sets up interesting parallels and a new turn for discourse between US homeland prisons and those used for the “Global War About Terror” (GWAT).

Relating to GWAT, Aaron Sandnes established a sound sculpture in which gallery visitors were subjected to the same pop songs used in Psych-ops by police and military interrogators.

Dread Scott‘s use of audio is intentionally to give silenced men a voice. (Scott has talked about the primacy of audio in his exhibition of prison portraits previously at Prison Photography).

Mabel Negrete collaborated with her brother incarcerated in Corcoran State Prison. She mapped out the floorplan of his cell as compared to her apartment bathroom. She then developed a dramatic dialogue in which she played both herself and her brother. (No images unfortunately.)

Traced – but essentially fictional – lines of structure are fitting for San Francisco, the city in which world-famous architect/installation artists Diller & Scofidio got their start with the architectural memories of the Capp Street Project. Negrete’s CV is extensive, she was instrumental in organising Wear Orange Day, a prisoner awareness action. Also check out her Sensible Housing Unit.

Cross-prison-wall collaborations are vital to the project as a whole; so much so, that without input from prisoners, the entire enterprise would fall short. Primarily, it is the men of the Arts in Corrections: San Quentin run by the William James Association who deliver acrylics and oils of optimistic colour and profound introspection. More here.

Collaboration as delivered in a multimedia and digital format comes by way of Sharon Daniel’s Public Secrets. Public Secrets “reconfigures the physical, psychological, and ideological spaces of the prison, allowing us to learn about life inside the prison along several thematic pathways and from multiple points of view.”

In closing, it is worth noting that San Quentin prison (only 12 miles north of San Francisco) has one of the few remaining prison arts programs in the state following 20 years of cut backs. The works in Prison/Culture challenge – as Deborah Cullinan & Kurt Daw, in their foreword, suggest – “traditional boundaries between inside and outside, between professional and amateur, between institutions and people” and, “by juxtaposing work by professional artists with artists who are working inside a prison, this book challenges us to rethink notions of community and culture.”

Prison/Culture is simultaneously a consolidation of achievement, a fortification of resources and celebration of resistance. This may be a book with a Californian focus, but it has national and international relevance. Succinct, well researched, egalitarian and lively. For me, Prison/Culture is the best collection of works by any US prison reform art community up until this point in history.

The resource list of over 80 organisations at the back of the book (page 92) is ESSENTIAL reference material for anyone looking to commit energies into prison art programs. All told, this book is a must read for those interested in the artistic landscape of our prison nation. It powerfully exposes the vast gulf between criminal justice and social justice in US society.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Prison/Culture is published by City Lights, edited by Sharon E. Bliss, Kevin B. Chen, Steve Dickison, Mark Dean Johnson and Rebeka Rodriguez.

Read a Daily Kos review here, and view images from a 2009 exhibition here.

City Lights Celebrates the Release of Prison/Culture

On Thursday, May 6 at 7:00 pm, join Steve Dickison, Jack Hirschman, Ericka Huggins, and Rigo 23 for a reading and book release celebration at City Lights Books. Tune in to KQED Forum at 9:00 am PDT the morning of the event for an interview with the book’s editors and contributor Angela Davis.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Images (from top): PRISON/CULTURE book front; Sandow Birk; Deborah Luster; Exhibition views of The House That Herman Built; Alex Donis; Alex Donis; Alex Donis; Julie Green; Julie Green; Ronnie Goodman, San Quentin inmate, displays his work; and ‘Public Secrets’ screenshot.

Casey Orr‘s Comings & Goings is an inquiry into movements and migration. Comings & Goings is a photographic series in three parts. Families considers the prisoners and their loved ones at Her Majesty’s Prison Leeds, UK.

Caged Birds depict the imported pigeons and parrots and parakeets of West Yorkshire, while Migrant Women portrays the recent newcomers to Orr’s county.

Orr insists the three parts be considered together – they are a whole, cannot be separated, and toy with the idea of interconnectedness Orr has grappled with throughout her career.

Comings & Goings proposes that foreign and indigenous are not so far apart. As Orr puts it we all share “a desire to be free, an instinct to nest, to seed, to move and be alive”.

Orr’s work requires time and care to navigate – it is as delicate as it is pioneering. Prints from all three parts were displayed was on the outside walls of HMP Leeds. It was the first time the wall of a UK prison has been used as a gallery space.

I wanted to know a bit more and so emailed Casey.

Q & A

Why did you decide to incorporate H.M.P Leeds into your Comings and Goings project? Was it the subject or the challenge of working within a prison or a mixture of the two?

My photographic work makes connections to my community and to my experience of living here in Armley, Leeds. My interest in the prison came from other projects I’ve done here. I’m always looking for the connection between the things and people I photograph, the systems that operate and seem to run through everything.

The town of Armley is very much built from the systems of power that came through the Industrial Revolution; Armley Mills, once the largest mill in the world, is now the Leeds Industrial Museum; the Leeds Liverpool Canal is now used for leisure; and the incoming migrant communities are moving from their countries for very contemporary reasons, the jobs available to them (and everyone else in Leeds) having much more to do with information technology than agriculture or textiles.

Within all of this movement, stands HMP Leeds, known locally as Armley Jail. It sits on a hill, built in 1847, so that workers in the surrounding mills could be reminded of what would happen if they stepped out of line. The prison (along with a massive, imposing Victorian church) is one of the few buildings around here still used for its original purpose.

The systems of power associated with the panopticon are still firmly in use in the prison. The prison walls, inside my community, seem to be impenetrable, and enclose a community of thousands of prisoners and workers. My interest was in the walls and how to find the connection into the prison, how to link the people inside with all of the flows of life going on outside.

I found that connection through families, through children. Hundreds of families visit their fathers, sons and brothers every week. The families and loved ones are a direct link with the communities outside. I wanted to exhibit the family portraits on the outside walls of the prison because the prison walls are such a architectural staple of this community they can become invisible, people can forget about them and the people behind them. The exhibition was shown on the interior walls as well so that the people inside were seeing the same thing, the same ideas were being shared; walls penetrated by ideas, and by art.

What negotiations did you go through to gain access? Who did you meet? How did it come about?

As a documentary photographer, very little of my time is actually taking pictures, mostly I am trying to gain access to people and places. Before contacting the prison direct I talked to many people in this community and finally went to the Jigsaw Project, the family support unit. From there I met many of the workers who support the families. They were sympathetic to my ideas and introduced me to the Head of Security. From there I met the Governor. All of this took many months. The work, finally shown on the walls as a public art installation as part of the West Leeds Arts Festival in 2009, went through many security checks.

How many times did you go to the visiting room to make the portraits?

I spent a few months in the visitors centre, talking to families, and asking who would like to be a part of the project. Obviously, I got to know them better than the prisoners who I met briefly during the sessions. I spent four days in total in the visiting room.

How did the prisoners and staff respond to your project?

Most people were really supportive of the idea. the thing about photography is that it has uses on many different levels. So this record of families I wanted to make could also be a part of their personal family archive. The fact that I’m able to give something back to people, something useful, like a family portrait, makes me feel better about the fact that I’m asking so much of people, to use their image for one of my ideas. Everyone involved received copies of whichever pictures they wanted from the sessions.

Has your work dealt with systems of detention in the past?

No, my work is about systems of power, photography being very much implicated in that, in the recording and filing of people. So the prison system is always implicated in that, as are all currents of capitalist power.

What’s next?

I’m just completing a book about Comings & Goings and another body of work following the traces of an age old ritual lingering in the English festivity of Bonfire Night.

BIO

Casey Orr (b.1968) is originally from Pennsylvania. She has lived in England for 14 years working as a freelance photographer and Senior Lecturer at Leeds Metropolitan University.Clients include Diva Magazine, Channel 4, EMI Records, Universal Records and Sports Council England. Orr has exhibited at the University of The Arts, Philadelphia, Pa. and Jen Bekman Gallery in New York. She is the recipient of an Arts Council England grant.

Read more about Orr’s exhibition at HMP Leeds in Armley at the Guardian.

JAIL GUITAR DOORS, headed by Billy Bragg, is a program that bring musicians and instruments to prisons in the UK. Thanks to a conversation between Bragg and the superintendent of Travis County Correctional Complex, JAIL GUITAR DOORS expanded its program into American jails.

Bragg and Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine among other musicians played live and collaborated with inmates at the Austin jail. The theory is one of music therapy. Bragg left six guitars inside the institution.

Bragg began JAIL GUITAR DOORS in 2007 naming the program after The Clash song of the same title. Since its inception, 32 prisons and more than 300 guitars have been part of the program.

Listen to the full story on NPR, visit the website for JAIL GUITAR DOORS, link up on the JGD’s Facebook page and a bit of local news here.

Klavdij Sluban and Jim Casper of LensCulture talked about Klavdij’s photography workshops in juvenile prisons across the world.

Early in the interview, Klavdij discloses his personal sadness that prisons exist. This emotion may be raw but it is not naive; Klavdij is balanced and realistic about what he can achieve with a camera in these specific distopias. He also says in seven words what I established this blog to say “Jails are a world to be discovered.”

He went to the prisons not as photographer, but as a concerned citizen. He realised if he were to go inside it would need to be with some reciprocity … so he took cameras and used them.

In terms of engagement and commitment to a population – the youth prison population of the world – Klavdij Sluban could and should be considered a ‘Concerned Photographer’. He deserves that loaded epithet.

I wouldn’t describe Melania Comoretto‘s portfolio Women in Prison as portraiture; it’s bigger, it’s emotional landscape.

Comoretto’s work tinged with sadness, possibly even resignation. Their circumstance may have dulled outward looking expectancy.

This work stands out, for me personally, as one of the finest photographic documents of women prisoners, globally. Women in Prison is charming and disarming. These are women whose words would likely shock us and yet they seem to know the weight of their own stories and captive futures. The reticence of Comoretto’s subjects, paired with the arresting gaze (when given), is a triumph.

Q&A

Where is this prison?

I photographed in two Italian prisons in Rebibbia and Trapani.

Why did you do a project there?

I wanted to investigate and understand how women could express their femininity and take care of their body in a situation of extreme marginalization.

The starting idea was to reflect the mental and psychological labyrinths and internal prisons that prevent human beings from living their lives freely. I asked myself, “What could be the extreme expression of this idea?” The answer; Prison.

What were the women’s lives like? Was their prison experience positive or negative?

The way the women live in prison depend on the prison in itself and how it is organised. It also depends on the personality and psychological attitude of the woman.

Most of them fall into depression; others react in a very active way. The body is the mirror of that. The more a women fall into depression the more she forget to take care of her body, that was the reason why I decided to focus on bodies and femininity.

Where are the women now?

Most of the women are still in Rebibbia and Trapani prisons. I shot this series of photos only in the last 10 months.

Were the women good portrait subjects? Did they want to be photographed?

They were very willing to speak and to be portrayed! They liked to spent time with me. They rarely have the chance to speak with someone who wants to listen deeply their stories.

Did they see your photograph prints?

I sent them each contact sheets.

In Italy what is society’s attitude toward prisoners and, specifically, female prisoners?

Unfortunately, in every city and country of the world, the social attitude towards prisoners is not very open-minded. They [societies] focus on the fact that prisoners are guilty and rarely on the fact that (in the majority of cases) that they had no chance because their lives started in very tragic conditions. Without any help it is very difficult for prisoners to change their destiny.

What was your experience on the project?

I understand how in some situations life does not leave you many chances to change.

Can the camera be a tool for rehabilitation?

I deeply believe it is. I don’t know if photography could be a tool of rehabilitation for the women. For me it was and is … so maybe [the camera] could be for them and for many other people. It prevents me from destroying myself and I believe it could have the same advantage for many other people!

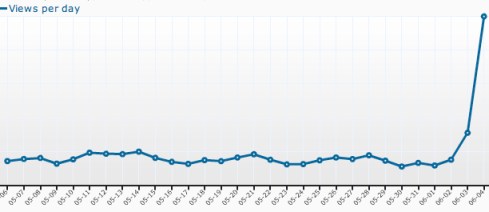

This week, Metafilter – among others – threw a stats-bomb at my wordpress account. The lure? Uncredited, amateur, pinhole photographs. No name … no logo.

The photography was by Girls in the Remann Hall Juvenile Detention Center, Tacoma, WA during a 2002 Steve Davis arts workshop.

These pictures really struck a chord. I am left to wonder what sort of interpretations are being made by viewers?

One thing I know is that a big CV, a big camera and fancy digijournalist turns may not be enough to secure soul-grabbing images. In fact, I’d argue it probably isn’t possible to compete with those nameless girls of Remann Hall.

Remann Hall girls 2002. Image created as part of a Steve Davis workshop. Pinhole camera.

Please contact Steve Davis for inquiries about image use and reproduction.

These images are the result of a collaboration between photographer Steve Davis and the girls of Remann Hall Juvenile Detention Center, Tacoma, Washington State in the US.

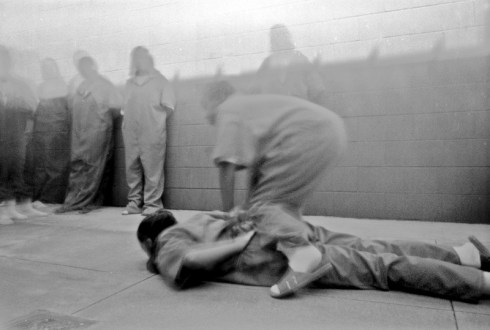

Davis was forced to think of the camera as a tool for different ends, essentially rehabilitative ends. For legal reasons and the protection of minors, Davis and his female students were not allowed to photograph each others faces. It became an exercise in performance as much as photography.

We see portraits of the girls with plaster masks, heads in their hands. The girls limbs outstretched made use of evasive gesture. The long exposures of pinhole photography resulted in conveniently blurred results.

PINHOLE PHOTOGRAPHY vs ROTE DOCUMENTARY MOTIFS

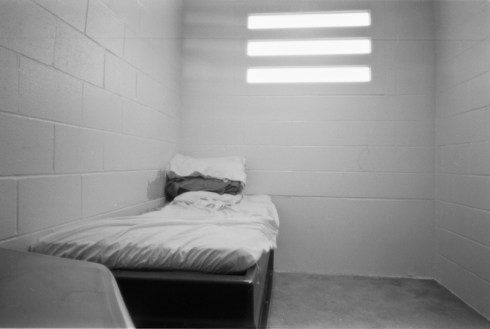

Photography in sites of incarceration often depicts amorphous, vanishing forms within stark cubes; it is usually black & white, and often from peep-hole or serving-hatch vantage points. When this vocabulary is used and repeated by photojournalists, visual fatigue follows fast.

Heterogeneous architecture doesn’t help the documentary photographer. Limited and repetitious visual cues make it tough to work in prisons. Images, shot through doors, by visitors only on cell-wings by special permission, are dislocating and sad indictments of systems that fail the majority of wards in their custody.

I celebrate all photography shining a light on the inequities of prison life. Having said that, very occasionally – only very occasionally, do I wish a “prison photographer” had expanded, waited or edited a prison photography project a little longer … but I do wish it.

Photojournalism & documentary photography have taken a battering from within and been asked some serious reflective questions. I don’t want to accuse photographers of complacency. To the contrary, my complaints are aimed at prison systems that so rarely allow the camera and photographer to engage with daily life of the institution.

Therefore, I stake two positions on the issue of motif/cliché. First, repeated clichés have developed in the practice of photography in prisons. Second, prison populations have had little or nothing to do with the creation, continuation or reading of these clichés.

As a general criticism, I would say photographers in prisons struggle to achieve original work. But, prisoner-photographers – whose experience differs vastly from pro-photographers, custodians and visitors – cannot be held to that same criticism.

WHEN THE PRISONER CONTROLS THE CAMERA

These images by the girls at Remann Hall are distinguished from the majority of prison documentary photography, because the inmate is holding the camera. When an inmate repeats a motif it is not a cliché.

These are images of all they’ve got; concrete floors, small recreation boxes, steel bars, plastic mattresses and chrome furniture … all the while lit brightly by fluorescent bulbs and slat windows. These aren’t images taken for art-careerism, journalism or state identification. These are documents of a rarefied moment when, for a while – in the lives of these girls – procedures of the County and State took back seat.

When a member from within a community represents the community, the representation is above certain criteria of criticism. A prison pinhole photography workshop has very different intentions than any media outlet. Cliche is not a problem here; it is a catalyst.

The simulation and reclamation of visual cliche (in this case the obfuscated hunched detainee) is doubly interesting. Why the frequent use of the foetal position? Why did the girls choose this vulnerable pose to represent themselves? Was it on advice? Was it mimicry? Was it part of a role they view for themselves? Why don’t they stand? Emotionally, what do they own?

As in evidence in some images, one hopes that some of these girls are friends. This selection of shots share a single predominant common denominator; the psychological brutality of cinder block spaces of confinement. Companionship seems like a small mercy in those types of space.

These photographs should knock you off your chair. I am in doleful astonishment. In the absence of faces, how powerful and essential are hands?

For now, consider how visual and institutional regimes square up.

Since the original publication of these images, they have been viewed tens of thousands of times. More than any other photographer – famous or not – these images by anonymous teenage girls have been by far the most popular ever featured on Prison Photography. That appetite shows that when prisons and struggle and creativity are presented in a meaningful way, images can be used as a segue into wider discussion of the underlying issues.

The Remann Hall project was done as a part of the education department program at the Museum of Glass in partnership with Pierce County Juvenile Court. This comment sums up the importance but also the fiscal fragility of these arts based initiatives:

“The Remann Hall project was an incredible project, which culminated in an outdoor installation at the museum and many of the participants coming to volunteer and participate in education programs at the museum after they were released. It was one of the many incredible programs I was lucky enough to be part of there. A book of poetry, artwork (and I think some of the photos in that link) was produced as well. The whole program was a great model for how arts organizations can do meaningful outreach in their communities. Unfortunately, the program was cut one year before the planned completion, due to budget concerns.”

[My bolding]